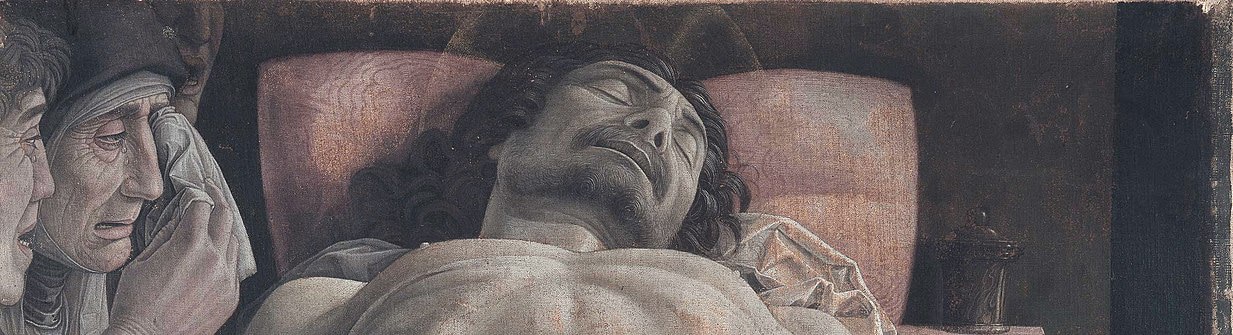

Jesus’ Death

The Scapegoat

Sunday, April 14, 2019

Palm Sunday

The ingenious Hebrew ritual from which the word “scapegoat” originated is described in Leviticus 16. On the Day of Atonement, a priest laid hands on an “escaping” goat, placing all the sins of the Jewish people from the previous year onto the animal. The goat was then beaten with reeds and thorns and driven out into the desert. It was a vividly symbolic act that helped to unite and free people in the short term. Instead of owning their sins, this ritual allows people to export them elsewhere—in this case onto an innocent animal.

French philosopher and historian René Girard (1923–2015) recognized this highly effective ritual across cultures and saw the scapegoat mechanism as a foundational principle for most social groups. The image of the scapegoat powerfully mirrors and reveals the universal, but largely unconscious, human need to transfer our guilt onto something or someone else by singling that other out for unmerited negative treatment. This pattern is seen in many facets of our society and our private, inner lives—so much so that we could almost name it “the sin of the world” (note that “sin” is singular in John 1:29). The biblical account, however, seems to recognize that only a “lamb of a God” can both reveal and resolve that sin in one nonviolent act.

We seldom consciously know that we are scapegoating or projecting. As Jesus said, people literally “do not know what they are doing” (Luke 23:34). In fact, the effectiveness of this mechanism depends on not seeing it! It’s automatic, ingrained, and unconscious. “She made me do it.” “He is guilty.” “He deserves it.” “They are the problem.” “They are evil.” We should recognize our own negativity and sinfulness, but instead we largely hate or blame almost anything else. Sadly, we often find the best cover for that projection in religion. God has been used to justify violence and hide from the parts of ourselves and our religions that we’d rather ignore. As Jesus said, “When anyone kills you, they will think they are doing a holy duty for God” (John 16:2).

Unless scapegoating can be consciously seen and named through concrete rituals, owned mistakes, shadow work, or “repentance,” the pattern will usually remain unconscious and unchallenged. The Scriptures rightly call such ignorant hatred and killing “sin,” and Jesus came precisely to “take away” (John 1:29) our capacity to commit it—by exposing the lie for all to see. Jesus stood as the fully innocent one who was condemned by the highest authorities of both “church and state” (Jerusalem and Rome), an act that should create healthy suspicion about how wrong even the highest powers can be. “He will show the world how wrong it was about sin, about who was really in the right, and about true judgment” (John 16:8).

This is what Jesus is exposing and defeating on the cross. He did not come to change God’s mind about us. It did not need changing. Jesus came to change our minds about God—and about ourselves—and about where goodness and evil really lie.

Reference:

Adapted from Richard Rohr, The Universal Christ: How a Forgotten Reality Can Change Everything We See, Hope For, and Believe (Convergent: 2019), 149-151.