Islam

Walk Gently on the Earth

Monday, September 24, 2018

During the Convivencia in Spain [711–1492], Jews, Christians and Muslims not only lived side by side in an atmosphere of religious tolerance but they also actively collaborated on some of the most important works of art, architecture, literature, mathematics, science, and mystical teachings in the history of Western culture. . . . The commitment to welcoming people of all faiths is still a beacon that shines from the heart of Islam. —Mirabai Starr [1]

Mature religions and individuals have great tolerance and even appreciation for differences. When we are secure and confident in our oneness—knowing that all are created in God’s image and are equally beloved—differences of faith, culture, language, skin color, sexuality, or other trait no longer threaten us. Rather, we seek to understand and honor others and to live in harmony with them. Karen Armstrong explains how this is a core teaching within Islam:

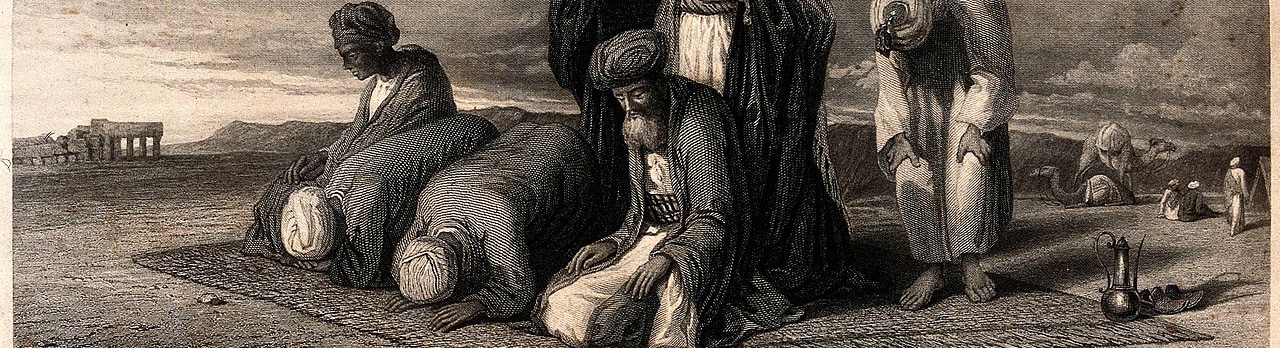

In the Qur’an, the people who opposed Islam when Muhammad began to preach in Mecca are called the kafirun. The usual English translation is extremely misleading: it does not mean “unbeliever” or “infidel”; the root KFR means “blatant ingratitude,” a discourteous and arrogant refusal of something offered with great kindness. . . . They were not condemned for their “unbelief” but for their braying, offensive manner to others, their pride, self-importance, chauvinism, and inability to accept criticism. [2] . . . Above all, they are jahili: chronically “irascible,” acutely sensitive about their honor and prestige, with a destructive tendency to violent retaliation. Muslims are commanded to respond to such abusive behavior with hilm (“forbearance”) and quiet courtesy, leaving revenge to Allah. They must “walk gently on the earth,” and whenever the jahilun insult them, they should simply reply, “Peace.” [3]

There was no question of a literal, simplistic reading of scripture. Every single image, statement, and verse in the Qur’an is called an ayah (“sign,” “symbol,” “parable”), because we can speak of God only analogically. The great ayat of the creation and the last judgment are not introduced to enforce “belief,” but they are a summons to action. Muslims must translate these doctrines into practical behavior. The ayah of the last day, when people will find that their wealth cannot save them, should make Muslims examine their conduct here and now: Are they behaving kindly and fairly to the needy? They must imitate the generosity of Allah, who created the wonders of this world so munificently and sustains it so benevolently. At first, the religion was known as tazakka (“refinement”). By looking after the poor compassionately, freeing their slaves, and performing small acts of kindness on a daily, hourly basis, Muslims would acquire a responsible, caring spirit, purging themselves of pride and selfishness. By modeling their behavior on that of the Creator, they would achieve spiritual refinement [what I would call growing in God’s likeness].

References:

[1] Mirabai Starr, God of Love: A Guide to the Heart of Judaism, Christianity and Islam (Monkfish Book Publishing: 2012), 211.

[2] Qur’an 7:75-76; 39:59; 31:17-18; 23:4547; 38:71-75.

[3] Qur’an 25:63.

Karen Armstrong, The Case for God (Alfred A. Knopf: 2009), 99-100.