Julian of Norwich

There Is No Anger in God

Thursday, May 14, 2020

Author and Episcopal priest Mary Earle explores the difficult questions that beset individuals during Julian’s time as well as our own. She writes,

In a social and cultural context [the fourteenth century was] so saturated with suffering and death, it is no wonder that many believers interpreted these [plagues] as clear signs of God’s anger with humanity. (Certainly, we still see vestiges of this way of interpreting events) . . . The underlying theology draws on a medieval doctrine known as substitutionary atonement . . . [which] held (as it still does today) that because of our many sins, we owe God a debt we can never repay—our burden of debt is so vast and we are finite. That is why Jesus, by dying on the cross, offers himself . . . as a sacrifice in order to satisfy the Father’s wrath. It is easy to see how this theology in its crudest form evolved into a belief in an angry and vengeful God, visiting humanity with punishing events. [1]

Thus in Julian’s day popular devotional art often depicted horrific scenes of the Last Judgment, scenes in which souls were being cast into hell, tortured endlessly by devils. Laymen and [lay]women of the fourteenth century would have constantly been wrestling with the “Why?” of suffering and the wrath of God. . . . When someone receives a terminal diagnosis, or a sudden death occurs, or a natural disaster devastates a region, the first question that occurs is usually, “Why me?”. . . The context out of which Julian writes, although in some ways so remote from our own, is one full of universal questions and themes. . . .

One of Julian’s most radical insights, with which I fully concur, is that there can be no wrath in God. Mary Earle continues,

Julian’s radical insistence that we know there is “no anger in God” [2] directs us all to look at ways in which we project our own bitterness, anger, and vengeance upon God. In a resolutely maternal way, she encourages us to grow up, to cast aside our immature and punitive images of God, and to be honest with ourselves about our own actions that have their roots in spiritual blindness. . . .

Julian tells us, again and again, in a variety of ways, that God is our friend, our mother and our father, as close to us as the clothing we wear. She employs homely imagery and language, the vocabulary of domesticity, to tell us her experience. At the same time, she demonstrates a degree of sophisticated theological language. Julian is firm and steady on these points:

- God is One.

- Everything is in God.

- God is in everything.

- God transcends and encloses all that is made.

The only point I would add to that list from my own study of Julian is that she really believes that God is Love.

References:

[1] I am thankful that in my own Franciscan tradition, John Duns Scotus (c. 1266–1308) taught us an “alternative orthodoxy” that we often call “at-one-ment.” You can read Chapter 12 of my book The Universal Christ for a greater explanation of the topic.

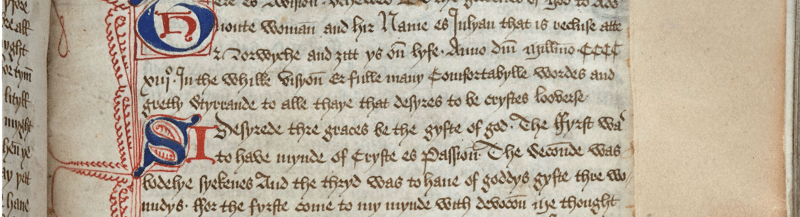

[2] Julian of Norwich, The Fifth Revelation, ch. 13 (Long Text).

Adapted from Mary C. Earle, Julian of Norwich: Selections from Revelations of Divine Love—Annotated & Explained (SkyLight Paths: 2013), xxi-xxii, xxiv.