Gender and Sexuality: Week 2

Franciscan Feminism

Thursday, April 26, 2018

While my religious order is far from perfect, I appreciate how Franciscanism has in so many subtle ways honored and embraced the feminine side of things. One scholar rightly says that St. Francis “without having a specific feminist program . . . contributed to the feminizing of Christianity.” [1] French historian André Vauchez, in his critical biography of Francis, adds that this integration of the feminine “constitutes a fundamental turning point in the history of Western spirituality.” [2] I think they are both onto something, which creates the distinctiveness and even the heart of the Franciscan path. In so many ways, we were not like the classic pattern of religious orders.

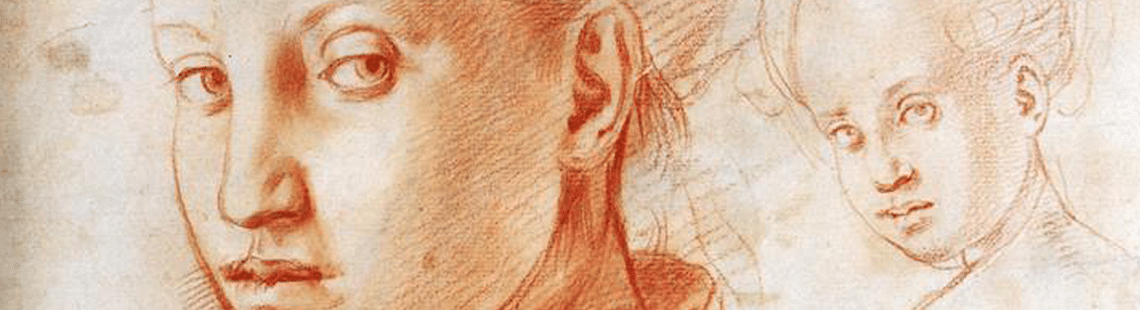

St. Clare (1194-1253) is clearly the Franciscans’ archetypal symbol of the feminine, and yet the very male St. Francis (1182-1226) almost supernaturally exemplifies it—as a man. In my view, Franciscanism integrated the feminine element into a very patriarchal and overly masculinized Roman Church, the harsh male spirituality of the desert, and an overscheduled spirituality in most monasteries.

Franciscanism integrated the feminine both on the level of imagination and in practical ways too. It created new “softer” names for roles and functions, a more familial structure than a hierarchical one. We do not make our decisions top down, but communally in chapters (as do most communities now). Francis forbad us to use any titles implying up and down, like prior, abbot, or superior.

Happy and healthy Franciscans seem to present a combination of lightness of heart and firmness of foot at the same time. By this I mean that they do not take themselves so seriously, as upward-bound men often do; they often serve with quiet conviction and personal freedom as many mature women do.

I see this synthesis of both lightness and firmness as a more “feminine” approach to spirituality, beautifully exemplified in both Clare and Francis in different ways. It is a rare combination, so much so that it might seem a kind of holy foolishness. Androgyny is invariably a threatening Third Force if we are over-identified with one side or the other.

Clare asks from the papacy that she be allowed to found her community on her privately conceived and untested ground that she calls a “privilege of poverty.” Then she waits patiently on her deathbed for the papal bull to arrive. She knows she will win, even though there was no precedent for women’s religious communities without dowries or patronage systems being able to sustain themselves.

As to Francis, he twirls around like a top at a crossroads to discern which way God wants him to go, and then sets off with utter confidence in the direction where he finally lands. Neither of these ways are classic Catholic means of discernment, decision-making, or discovering God’s will. Yet I believe the lightness of heart comes from contact with deep feminine intuition and with consciousness itself; the firmness of foot emerges when that feminine principle integrates with the mature masculine soul and moves forward with confidence into the outer world. These are just my interpretations, and you might well see it differently.

References:

[1] Jacques Dalarun, Francis of Assisi and the Feminine (Franciscan Institute: 2006), 127-154.

[2] André Vauchez, Francis of Assisi: The Life and Afterlife of a Medieval Saint (Yale University Press: 2012), 324-336.

Adapted from Richard Rohr, Eager to Love: The Alternative Way of Francis of Assisi (Franciscan Media: 2014), 119-120, 123-124.