Action and Contemplation: Part Three

The Prayer of Quiet

Tuesday, January 21, 2020

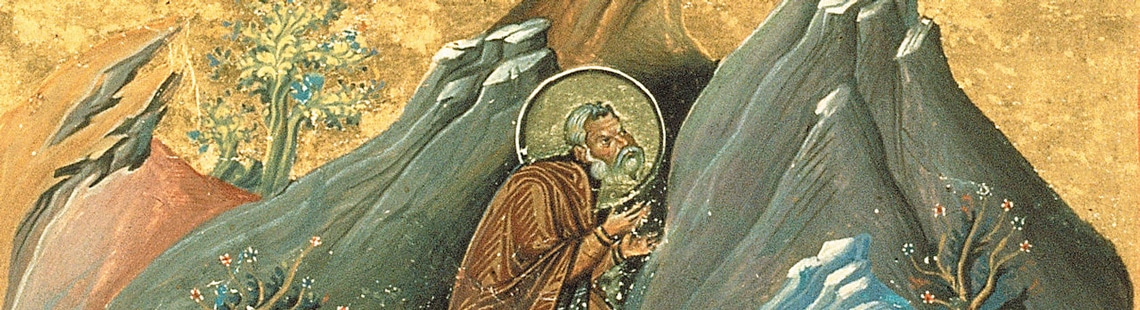

The Desert Fathers and Mothers withdrew from cities to the desert to live freely, apart from the economic, cultural, and political structure of the Roman Empire. At first, the empire persecuted the church, but in 313 CE, Constantine gave Christianity a privileged status, not out of enlightenment or goodwill but in service of uniformity and control. The Desert Fathers and Mothers knew, as we should today, that empire would be an unreliable partner. They recognized that they had to find inner freedom from the system before they could return to it with true love, wisdom, and helpfulness. This is a useful dynamic for all of us who want to act on behalf of the world. If we stay immersed in culturally acceptable ways of thinking and doing, Christianity’s deep, transformative power is largely lost.

So how do we find inner freedom? We can begin by noticing that whenever we suffer pain, the mind is always quick to identify with the negative aspects of things and replay them over and over again, wounding us deeply. This pattern must be recognized early and definitively. Peace of mind is actually an oxymoron. When you’re in your mind, you’re hardly ever at peace, and when you’re at peace, you’re never only in your mind. The early Christian abbas and ammas knew this and first insisted on finding the inner silence necessary to tame the obsessive mind. Their method was originally called the prayer of quiet and eventually referred to as contemplation. It is the core teaching in the early Christian period, but it has been emphasized much more in the Eastern Church than in the West.

In The Sayings of the Desert Fathers, Benedicta Ward relates this story, one of the briefest but most popular of all the desert sayings: “A brother came to Scetis to visit Abba Moses and asked him for a word. The old man said to him, ‘Go, sit in your cell, and your cell will teach you everything.’” [1] But you don’t have to have a cell, and you don’t have to run away from the responsibilities of an active life, to experience solitude and silence. In another story, Amma Syncletica said, “There are many who live in the mountains and behave as if they were in the town, and they are wasting their time. It is possible to be a solitary in one’s mind while living in a crowd, and it is possible for one who is a solitary to live in the crowd of his own thoughts.” [2]

By solitude, the desert mystics didn’t mean mere privacy or protected space, although there is a need for that too. The desert mystics saw solitude, in Henri Nouwen’s words, as a “place of conversion, the place where the old self dies and the new self is born, the place where the emergence of the [person] occurs.” [3] Solitude is a courageous encounter with our naked, most raw and real self, in the presence of pure Love. This level of contemplation cannot help but bring about action.

References:

[1] The Sayings of the Desert Fathers: The Alphabetical Collection, trans. Benedicta Ward, rev. ed. (Cistercian Publications: 1984, ©1975), 139.

[2] Ibid., 234

[3] Henri Nouwen, The Way of the Heart (Harper Collins Publishers: 2009), 27.