Eastern Christianity

Universal Restoration

Thursday, September 13, 2018

The shape of creation must somehow mirror and reveal the shape of the Creator. We must have a God at least as big as the universe, or else our view of God becomes irrelevant, constricted, and more harmful than helpful. The Christian image of a torturous hell and God as a petty tyrant has not helped us to know, trust, or love God. God ends up being less loving than most people we know. Those attracted to the common idea of hell operate out of a scarcity model, where there is not enough Divine Love to transform, awaken, and save. The dualistic mind is literally incapable of thinking any notion of infinite grace.

The common view of hell and a quid pro quo God is based not on Scripture but on Dante’s Divine Comedy—great poetry, but not good theology. The word “hell” is not mentioned in the first five books of the Bible. Paul and John never once use the word. Most of the Eastern fathers never believed in a literal hell, nor did many Western mystics.

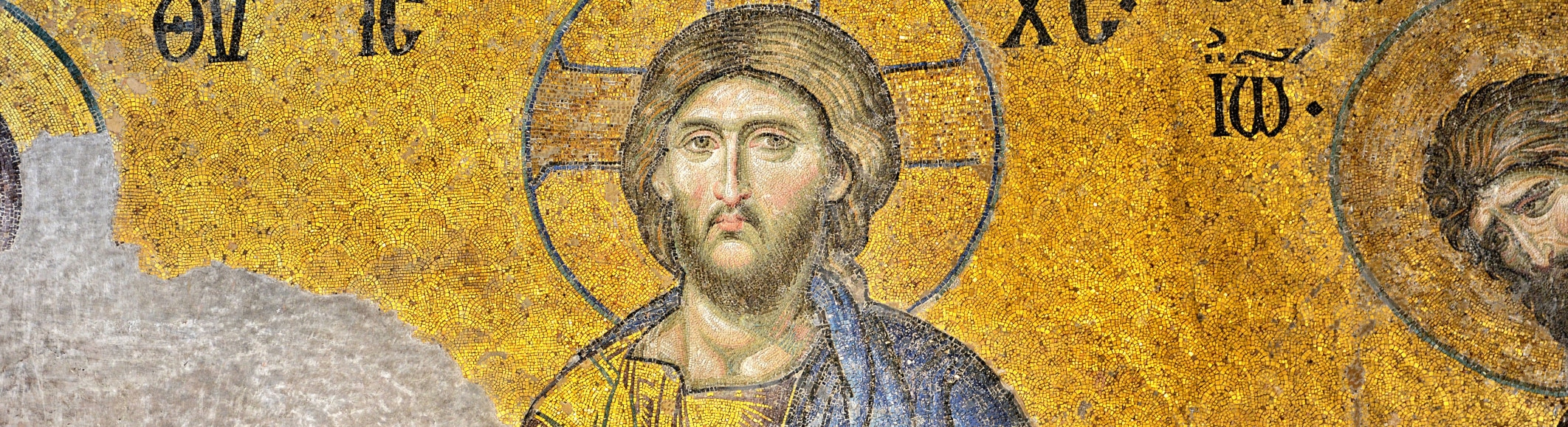

Eastern fathers such as Origen, Clement of Alexandria, Gregory of Nyssa, Jerome, Peter Chrysologus, Maximus the Confessor, and Gregory of Nazianzus taught some form of apocatastasis instead, translated as “universal restoration” (Acts 3:21). Origen writes:

An end or consummation is clearly an indication that things are perfected and consummated. . . . The end of the world and the consummation will come when every soul shall be visited with the penalties due for its sins. This time, when everyone shall pay what he owes, is known to God alone. We believe, however, that the goodness of God through Christ will restore [God’s] entire creation to one end, even [God’s] enemies being conquered and subdued. [1]

Morwenna Ludlow describes Gregory of Nyssa’s two arguments for universal salvation as:

a fundamental belief in the impermanence of evil in the face of God’s love and a conviction that God’s plan for humanity is intended to be fulfilled in every single human being. These beliefs are identified with 1 Corinthians 15:28 [“so that God may be all in all”] and Genesis 1:26 [we are made in God’s “image and likeness”] in particular, but are derived from what Gregory sees as the direction of Scripture as a whole. [2]

If we understand God as Trinity—the fountain fullness of outflowing love, relationship itself—there is no theological possibility of any hatred or vengeance in God. Divinity, which is revealed as Love Itself, will always eventually win. God does not lose (see John 6:37-39). We are all saved by mercy. Any notion of an actual “geographic” hell or purgatory is unnecessary and, in my opinion, destructive of the very restorative notion of the whole Gospel.

Knowing this ahead of time gives us courage, so we don’t need to live out of fear, but from an endlessly available love. To the degree we have experienced intimacy with God, we won’t be afraid of death because we’re experiencing the first tastes and promises of heaven already. Love and mercy are given undeservedly now, so why would they not be given later too? As Jesus puts it, “God is not the God of the dead, but of the living—for to God everyone is alive” (Luke 20:38). In other words, growth, change, and opportunity never cease, even during and after death! Why would it be otherwise?

References:

[1] Origen, On First Principles, trans. G. W. Butterworth (Ave Maria Press: 2013), 69-70.

[2] Morwenna Ludlow, Universal Salvation: Eschatology in the Thought of Gregory of Nyssa and Karl Rahner (Oxford University Press: 2000), 239.

Adapted from Richard Rohr, Hell, No! (Center for Action and Contemplation: 2015), CD, MP3 download.