Modern Peace Makers

Martin Luther King: Redemptive Suffering

Tuesday, October 27, 2015

I am convinced that the universe is under the control of a loving purpose and that in the struggle for righteousness man has cosmic companionship. —Martin Luther King, Jr. [1]

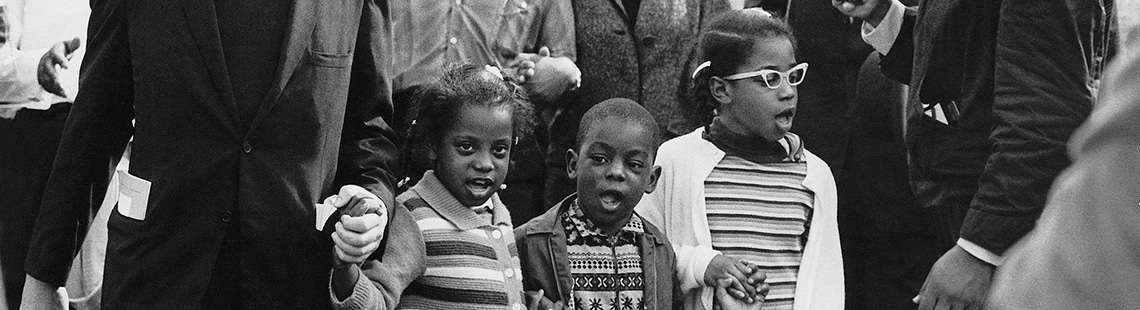

Martin Luther King, Jr., (1929-1968) learned from Gandhi how Jesus’ teachings could be applied beyond the level of individual relationships to the whole world of social change. Like Gandhi, King knew that to be effective, nonviolence must begin with the individual; but it can’t stop there. Ta-Nehisi Coates observes that as King preached nonviolence to young African-American men, they challenged him to confront the United States’ use of violence in the Vietnam War. Coates shares, “If we really, really do believe in nonviolence, it’s not just for people out in the street hurling rocks. It’s also for legislators, it’s also for senators and it’s also for presidents.” [2] Nonviolence isn’t only for people who lack power, but equally for the powerful—who are even more afraid of it, for fear of not getting re-elected.

As the school of Paul says in several places, our fight is really against “the principalities and powers” (Ephesians 6:12)—a pre-modern phrase for institutions, nation states, and corporations, which are always organized in their own favor. The problem is not first of all “the flesh” or personal sin, but systemic evil and structural, disguised violence. King’s nonviolent actions allowed him, like Jesus, to ask question of the demons: “What is your name?” And they were forced to reveal themselves as a “Legion because they were many” (Luke 8:30). As King writes:

It is evil we are seeking to defeat, not the persons victimized by evil. Those of us who struggle against racial injustice must come to see that the basic tension is not between races. . . . The tension is at bottom between justice and injustice, between the forces of light and the forces of darkness. . . . At the center of nonviolence stands the principle of love. . . . To retaliate with hate and bitterness would do nothing but intensify the hate in the world. [3]

Like Gandhi, King was hopeful because he saw God’s love as the foundation of existence. In King’s words:

The method of nonviolence is based on the conviction that the universe is on the side of justice. It is this deep faith in the future that causes the nonviolent resister to accept suffering without retaliation. . . . This belief that God is on the side of truth and justice comes down to us from the long tradition of our Christian faith. There is something at the very center of our faith which reminds us that Good Friday may reign for a day, but ultimately it must give way to the triumphant beat of the Easter drums. [4]

We must never forget that there is something within human nature that can respond to goodness, that man is not totally depraved; to put it in theological terms, the image of God is never totally gone. [5]

Jesus undercut the basis for all violent, exclusionary, and punitive behavior. He became the forgiving victim, so we would stop creating victims ourselves. He became the falsely accused one, so we would be careful whom we accuse.

Worldly systems actually prefer violent partners to nonviolent ones; it gives them a clear target and a credible enemy. Empires are relieved to have terrorists to shoot at and Barabbas figures loose on the streets. Types like Jesus, Martin Luther King, and Gandhi make difficult enemies for empires. They cannot be used or co-opted.

The powers that be know that nonviolent prophets are a much deeper problem because they refuse to buy into the very illusions that the whole empire is built on, especially “the myth of redemptive violence.” Like Jesus, they live instead a life of redemptive suffering. [6] This is the cosmic shift initiated by the Gospel, but historically followed by a rather small minority of Christians (martyrs, Mennonites, Amish, Quakers, conscientious objectors, etc.).

“The nonviolent resister is willing to accept violence if necessary, but never to inflict it,” King writes. “Generously endured suffering for the sake of the other has tremendous educational and transforming possibilities.” [7, emphasis mine] Almost more than anything else! It is not that suffering of itself is “good.” It is just that one’s newfound intimacy with life, with others, and with God is usually attained in no other way. Please trust me on that. It is precisely what we mean when we say that “the cross saves the world.” Jesus was the paradigm and model for our redemptive suffering.

Gateway to Silence:

“Be the change you wish to see in the world.” —Gandhi

References:

[1] Martin Luther King, edited by James Melvin Washington, A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings of Martin Luther King, Jr. (Harper & Row: 1986), 40.

[2] Ta-Nehisi Coates in an interview with Robert Siegel, 1 May 2015, National Public Radio, npr.org/2015/05/01/403597684/atlantic-staffer-criticizes-calls-for-nonviolence-in-baltimore.

[3] King and Washington, A Testament of Hope, 8.

[4] Ibid., 9.

[5] Ibid., 48.

[6] Adapted from Richard Rohr, Things Hidden: Scripture as Spirituality (Franciscan Media: 2010), 152.

[7] King, “An Experiment in Love,” A Testament of Hope, 18.