Franciscan Way: Part Two

Francis and the Sultan

Thursday, October 10, 2019

The connection that Francis of Assisi made with “the enemy” in his lifetime may be his most powerful statement to the world about putting together the inner life with the outer, and all of the resulting social, political, and ethnic implications. He also offers an invitation to—and an example for—the kind of interfaith dialogue that provides a much-needed “crossing of borders” so that we can understand people who are different from us. Francis’ kind of border crossing is urgently needed in our own time, when many of the same divisive issues are at still at play between Christians and Muslims and so many other religious, political, national, and racial groups.

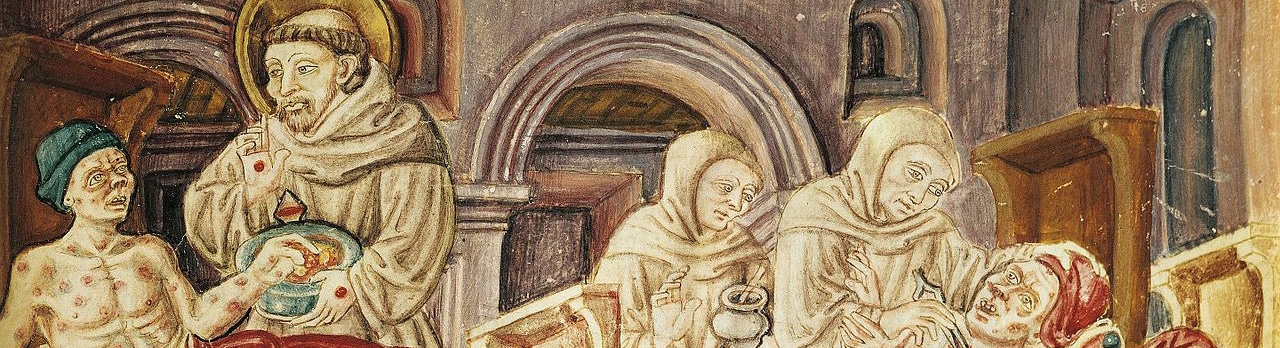

Francis made several attempts to visit the troops fighting in the Holy Land, and in September 1219 he met with Sultan Malik al-Kamil in Damietta, Egypt. [1] At the time, in thirteenth-century Europe, there was almost no actual knowledge of Islamic culture or religion, but rather only stereotypes of “the enemy.” The vast majority of voices in the Western Church—popes at their lead—had been swept up in the fervor of the anti-Islamist Crusades which began in 1095. (There were nine Crusades; Francis intervened in the fifth.) Popes repeatedly used promises of eternal life and offered indulgences and total forgiveness of sin for those who would fight these “holy wars” that were then backed up by kings and official Crusade preachers. Hardly anyone objected or recognized that this was a major abuse of power and of the Gospel.

Francis left his own culture at “great cost” to himself to go to the Sultan, to enter the world of another—and one who was considered a public enemy of his world and religion. Francis seems to have tried three times, but only succeeded in getting to his goal on the third try. On this attempt, he went to Egypt primarily to tell the Christian troops that they were wrong in what they were doing.

Francis’ humility and respect for the other, and thus for Islam, gained him what seems to have been an extended time, maybe as much as three weeks, with al-Kamil. The Sultan sent him away with protection and a gift (a horn that was used for the Muslim call to prayer), which suggests they had given and received mutual regard and respect. This horn can still be seen in Assisi.

With great wisdom, Francis was able to distinguish between institutional evil and the individual who is victimized by it. He still felt compassion for the individual Christian soldiers, although he objected to the war itself. He realized the folly and yet the sincerity of their patriotism, which led them, however, to be un-patriotic to the much larger Kingdom of God where Francis placed his first and final loyalty.

References:

[1] Three studies—all very accessible—succeed in bringing this unparalleled historical event out of the shadows of pious hagiography into the realm of very real social, political, and spiritual importance: Kathleen Warren, In the Footsteps of Francis and the Sultan: A Model for Peacemaking (Sisters of St. Francis: 2013); Paul Moses, The Saint and the Sultan: The Crusades, Islam, and Francis of Assisi’s Mission of Peace (Doubleday: 2009); George Dardess and Marvin L. Krier, In the Spirit of St. Francis and the Sultan: Catholics and Muslims Working Together for the Common Good (Orbis Books: 2011).

Adapted from Richard Rohr, Eager to Love: The Alternative Way of Francis of Assisi (Franciscan Media: 2014), 153-154, 155-156, 157-158.