Jung: Week 2

Becoming Whole

Sunday, October 11, 2015

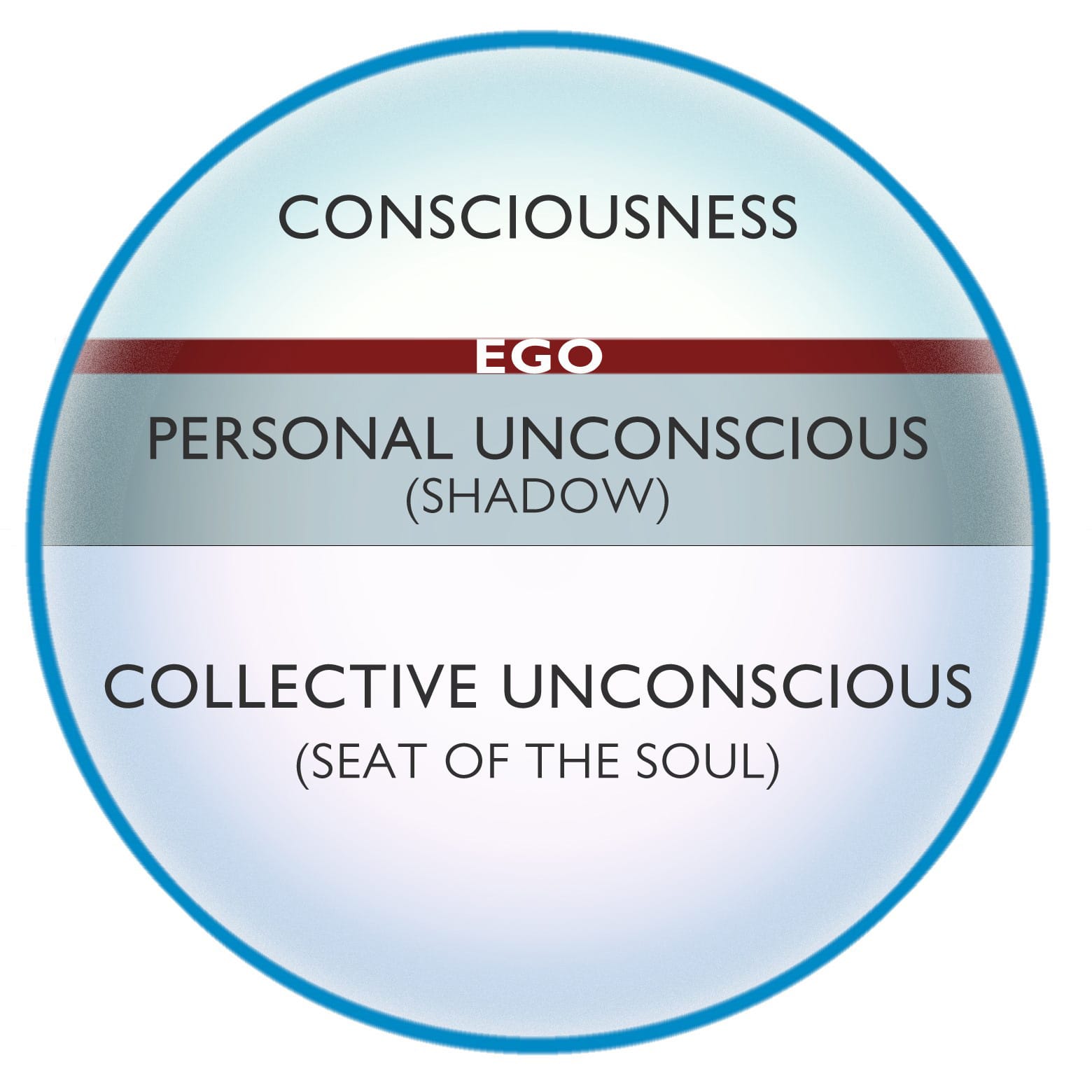

Most people live out of the top third of the circle, which is ironically called “consciousness.” This is what I know, what I think, what I have experienced, what I consider to be “me.” The ego, shown here as a bold red line, is that part of the self structure that wants to be significant, central, important, and right. It is highly defended and self-protective by its very nature. The irony and paradox is that if you stay above this line, you are largely unconscious, and not truly conscious at all!

The ego wants to eliminate all bothersome, humiliating, or negative information in order to “look good” at all costs. Jesus calls this self an “actor,” a word he uses fifteen times in Matthew’s Gospel. This is usually translated from the Greek as “hypocrite.” The ego wants to keep you tied to your easy and acceptable levels of knowledge. It encourages you to live only from this conscious self, which as we said, is really not conscious at all. Therapy, suffering, prayer, and mysticism encourage you to drop into the personal and collective unconscious.

The ego does not want you going down into the “personal unconscious” or, as Jung would call it, your “shadow self.” The shadow includes all those things about yourself that you don’t want to see, are not yet ready to see, and you don’t want others to see. Our tendency is to try to hide or deny this shadow part of ourselves, even and most especially from ourselves. [1]

Jung questions: “How can I be substantial if I do not cast a shadow?” [2] He makes clear that the unconscious is not bad or evil, it is just hidden from us. Jung describes shadow also as “the source of the highest good: not only dark, but also light; not only bestial, semi-human and demonic, but superhuman, spiritual” and, in Jung’s word, “numinous.” [3] So that is why you dare not avoid the deep self. The wild beasts and the angels reside in the same wilderness, and it takes the Spirit to “drive” you there (Mark 1:13). You see why the mystics so emphasize going into the “darkness,” which can only be done by faith and immense courage. “It takes more courage to examine the dark corners of your own soul than it does for a soldier to fight on a battlefield,” says William Butler Yeats.

The bottom part of the circle is the deep unconscious, or what Jung calls the collective unconscious. There you are connected to everything and experience things in their unity. The collective unconscious holds images that fascinate people in all cultures, across times and places. Jung calls these universal truths and symbols—that are just waiting to be revealed—archetypes or ruling images. Jung believes that when you go deep enough you will find the numinous, the God archetype, the place where you are complete and whole. This may be what most people think of as the soul.

Truly conscious people are in touch with their unconscious, at least to some good degree. People who try to remain simply on the “conscious” level, overly defended by their ego, end up being very superficial and thus even dangerous—to themselves and all around them. Denying your shadow self allows you to unknowingly do very selfish and evil things—and even call it virtue (John 16:2-3). [4]

Gateway to Silence:

“The privilege of a lifetime is to become who you truly are.” —C. G. Jung

References:

[1] Adapted from Richard Rohr, Things Hidden: Scripture as Spirituality (Franciscan Media: 2008), 75-76.

[2] C. J. Jung, Modern Man in Search of a Soul (Harvest Book: 1933), 35.

[3] C. J. Jung, translated by R. F. C. Hull, edited by H. Read, M. Fordham, G. Adler, and William McGuire, Collected Works, Vol. 16, Bollingen Series XX, (Princeton University Press: 1976), 389.

[4] Adapted from Richard Rohr, unpublished “Rhine” talks (2015).